I recently ran into a situation at work where I needed to share a Git repo “across an air gap.” In other words, I needed to be able to read a Git repo without actually having read access to the Git repo. I did some research and found out that this can be done with Git Bundles, but when I tried to look for info on how to actually USE Git Bundles, I mostly found a lot of Stack Overflow and Reddit threads with 23 year old know-it-alls providing helpful tips like “That’s stupid. Why would you ever need to do this?” The answer is that you work for a financial services company and they are paranoid to give developers access to anything that exists on the internet. Anyway, enough ranting. I pieced together a method for using Git Bundles that worked well for me and I thought I’d share it.

So here’s the setup:

A company we’ll call “OutsourcePro” is hired to build an application for your employer, who we will call “FullTimeJob.” OutSourcePro uses private Bitbucket repos for all of their projects and they offer to provide the devs at FullTimeJob access to the repos for purposes of doing regular code reviews. Unfortunately, FullTimeJob is a financial services company and finds the internet to be too scary to allow anything like Git repo access. So, FullTimeJob’s developers are told that they can’t have the access.

OutSourcePro offers to send a giant zip file with the entire project at intervals of their choosing (rarely or never). But, FullTimeJob’s developers find out about Git Bundles. FullTimeJob devs tell OutSourcePro to provide a Git Bundle every Tuesday and Friday. This will allow FullTimeJob devs to review the changes without needing to read every single line of code to figure out what’s different. FullTimeJob’s security experts agree that receiving a giant zip file via email twice a week is more secure than accessing a private Git repo directly (um… okay). Great! But, now what? The interwebs have very little useful info on how Git Bundles actually work. So, a developer at FullTimeJob does some experimenting and comes up with a plan:

Method 1: One-way Traffic

This assumes that all development work is being done by OutSourcePro and that FullTimeJob’s developers only need read-access for code reviews and whatnot. Developers at FullTimeJob will not be committing or pushing any code.

- OutSourcePro creates a private Git repo (on Github, Bitbucket, or somewhere else).

- FullTimeJob creates a corresponding Gitlab repo on their proprietary, enterprise Git server.

- OutSourcePro does daily work and pushes ALL changes to to their private Git repo (including work in progress)

- On Tuesdays and Fridays, an OutSourcePro developer pulls ALL commits from ALL branches to their local repository.

- The OutSourcePro developer creates a git bundle:

git bundle create outsourcepro_DDMMYY.bundle –all

- The OutSourcePro emails the bundle to FullTimeJob

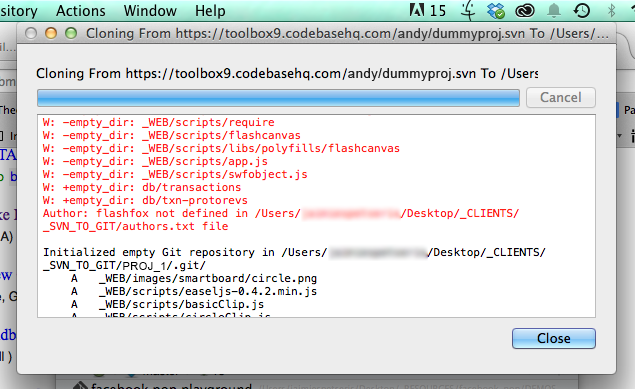

- A FullTimeJob developer copies the bundle to their Desktop and clones it to a new folder:

git clone /Users/FullTimeJobDev/Desktop/outsourcepro_MMDDYYYY.bundle

- This will clone it into a folder named for the bundle: outsourcepro_DDMMYYYY

- The FullTimeJob Developer should then point the origin of the new local clone to their private enterprise Git server:

git remote set-url origin https://ftjgitlab.com/project/repo-name.git

- Once the origin has been set, the FullTimeJob developer can push all changes from the local clone to the enterprise remote.

- Once all the changes have been pushed, the local clone should be deleted from the FullTimeJob developer’s Desktop.

- Now, all FullTimeJob developers can fetch/pull the changes from the enterprise remote to their local repos.

Basically, this process allows you to make a duplicate of the Git repository on your own server and keep up with the changes being made by the OutSourcePro team.

Method 2: Two-way Traffic

What if developers on BOTH teams needed to make changes to the code? This use case is actually very similar, with both teams sending Git bundles to each other and following the process above. But there are a few tips I will suggest to make it easier:

- Don’t cross the streams! Before starting the project, decide what each team will name the branches on their Git repos, and make sure that the two teams are ALWAYS USING SEPARATE BRANCHES. Same-named branches will cause chaos. In our example:

- FullTimeJob will eventually own all of this code, so they name their main branches “dev” and “master.” All other branches on their end will be named “ftj-something.”

- OutSourcePro will eventually hand over all of the code, so they name their main branches “osp-dev” and “osp-master.” All other branches will also be named “osp-something.”

- Decide who will do the merging into the final repo branches. Again, in our case:

- FullTimeJob will own the code and the final project will reside in the “dev” and “master” branches create by FullTimeJob. So, only FullTimeJob developers are allowed to merge code into these branches.

- Similarly, OutSourcePro owns all of the “osp-” branches and only OutSourcePro devs are allowed to merge anything into those branches.

- Both teams should be merging the other team’s work into their branches regularly and resolving the conflicts.

- Nail down specific times when new bundles will be delivered to each team so that the syncing and merging can be done at scheduled times.

That’s it! I suggest testing this out internally before you try to do it in a real-life scenario. Have two developers act as members of the two teams. One developer can create a git bundle and send it to the second dev, who will follow the process of trying to duplicate it to a new repository. Then, have the first dev make some commits and send another Git bundle to the second dev who tries to add the changes to their duplicate repo. Good Luck and let me know if I missed any important details!

I see a lot of forum threads and blog posts on “which is better – Subversion or Git? The real question should be “which is better for my workflow – SVN or Git?” I’ll attempt to help you sort it all out.

I see a lot of forum threads and blog posts on “which is better – Subversion or Git? The real question should be “which is better for my workflow – SVN or Git?” I’ll attempt to help you sort it all out. Which do I prefer? Again, it depends. For my projects at work, Git has been great (unless I need to version a bunch of videos, Then, it stinks). I have a handful of personal projects that I prefer to handle with SVN. I have a USB flash drive on my keychain that contains the remote SVN repositories. So, no matter where I am or which computer I’m using, I can update from the USB drive and work, even if I have no internet access. You can do this with Git too, but since I’m the only developer on these projects, I don’t need the fancy-schmanciness of Git and SVN is less hassle.

Which do I prefer? Again, it depends. For my projects at work, Git has been great (unless I need to version a bunch of videos, Then, it stinks). I have a handful of personal projects that I prefer to handle with SVN. I have a USB flash drive on my keychain that contains the remote SVN repositories. So, no matter where I am or which computer I’m using, I can update from the USB drive and work, even if I have no internet access. You can do this with Git too, but since I’m the only developer on these projects, I don’t need the fancy-schmanciness of Git and SVN is less hassle.